The school year is over. The “Nation’s Report Card” has been published. The results aren’t good.

The youth of America are struggling to answer questions about history and civics.

Between 2018 and 2022, U.S. history scores on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) fell by an average of 5 points on a 500-point scale. Scores in civics fell by 2 points on a 300-point scale.

Peggy Carr, commissioner of the National Center of Educational Statistics, said,

Self-government depends on each generation of students leaving school with a complete understanding of the responsibilities and privileges of citizenship. But far too many of our students are struggling to understand and explain the importance of civic participation, how American government functions, and the historical significance of events. These results are a national concern.

For context, NAEP test scores in history and civics have never been very good.

Scores on the 2022 civics test are at the same level as when the test was first administered in 1998. Average eighth grade scores have hovered around 150 on the 300 scale, peaking at 154 in 2014 before sliding back down to 150 in 2022.

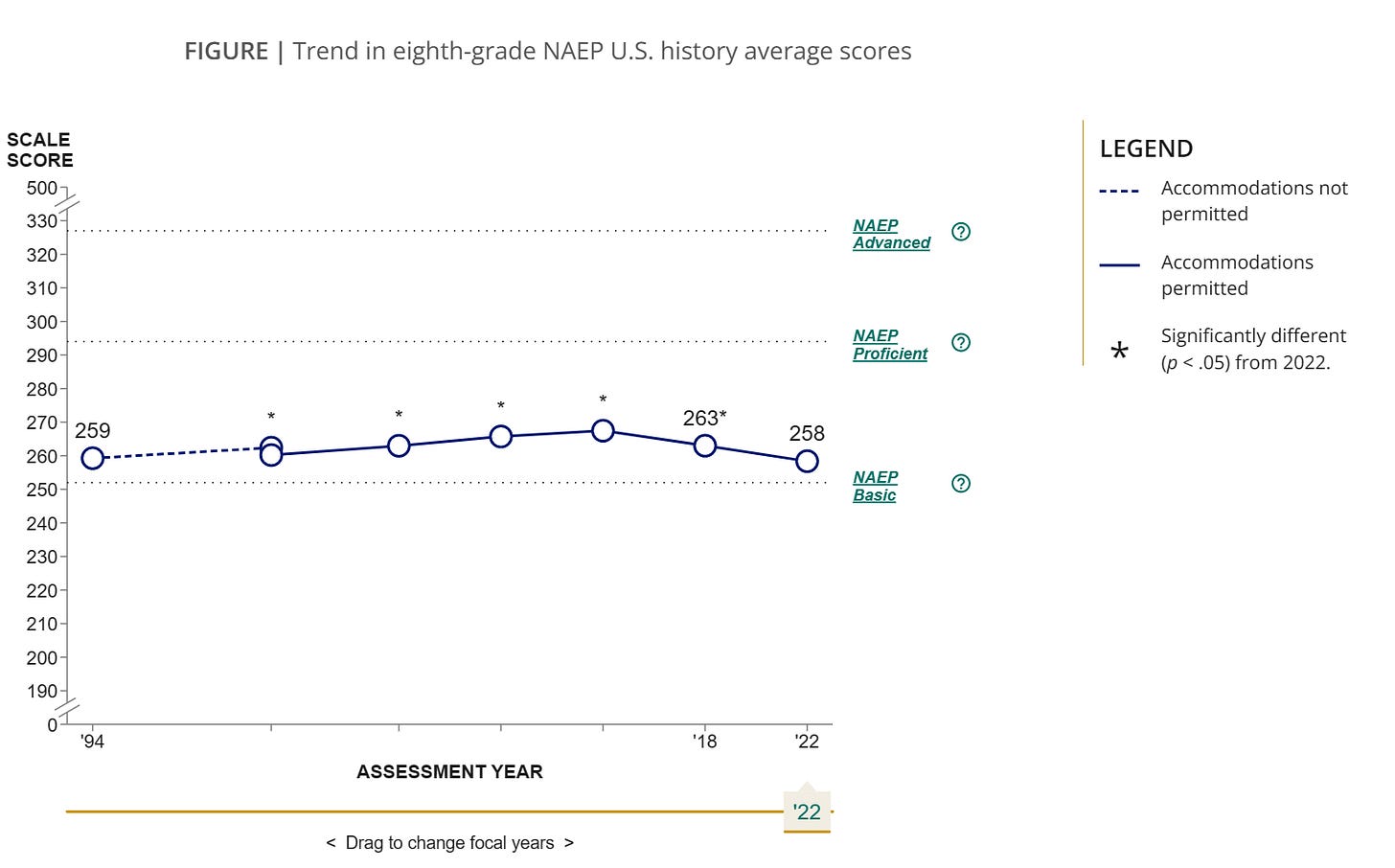

In U.S. history, average scores on the first administered test in 1994 were 259 out of 500. The average scores increased gradually, up to 267, before sliding back down to 258 in 2022.

It’s not surprising these test scores are consistently flat.

We don’t emphasize history or civics in public schools, because there is a federal mandate to conduct state testing in English and math (but not social studies).

If we want to raise test scores in history and civics, the obvious solution would be to spend more time teaching the history and civics concepts that will be tested. Other proposed solutions include creating a better infrastructure of high-quality social studies instructional material and using more social studies texts for statewide reading assessments.

I support both of these solutions. I’ve written previously about a few other ideas for improving civics education. We can and should do a better job teaching history and civics to the youth of America.

However, any healthy reform of civics education must be led by political leaders who actually care about the principles of self-government and the values that underpin the Constitution.

Civic culture is a dynamic ecosystem. The classroom is an important incubator of civic virtue, but the words and actions of adults in the public sphere are also pivotal. Preaching civic virtue in the classroom feels antiquated in an era of cultural warfare and partisan brinksmanship.

On the one hand, knowledge of American history is critical to preserving self-government. On the other hand, a group of U.S. senators who graduated from Ivy League schools opposed certifying the 2020 presidential election based on zero credible evidence of election fraud.

Can the vice president unilaterally reject states' Electoral College votes, sending them back to state legislators to override their voters? Classroom teachers would say no, that’s not how it works. But some highly educated people argued that yes, if Donald Trump loses, then his vice president can do such a thing, and we’ve got some “alternate” electoral votes ready to go.

The justification for such radical brinksmanship, and part of the reason why Trump still stands a chance at the presidency in 2024, is that the right wing perceives the left wing to be an existential threat to the republic. The thinking goes along these lines: The left wants to rewrite the history of this country in order to demonize the Founding and usher in a Marxist dystopia. Only a strongman willing to fight beyond the boundaries of polite society can defeat this threat.

This is not a comprehensive analysis of American politics. It would take a long time to itemize and compare the civic transgressions of the different political factions over the years. Suffice it to say the state of the union feels wobbly, lately, and good civic role models are more likely to get death threats than to get reelected.

In the old days, a classroom teacher might play a presidential debate in class and then discuss the policy disagreements. These days, a presidential debate might not be suitable for a young audience.

These days, it’s much safer for a classroom teacher to avoid current events altogether. In a bitterly divided nation, the basic endeavor to teach social studies is fraught with controversy.

Maybe the sorry state of our union can be blamed on the dismal state of our education system. Maybe if we did a better job teaching history and civics, the American people wouldn’t be so susceptible to radical demagogues. Maybe if the population was more discerning, we could have a real debate about reforming our nation’s finances, for example, rather than absurd political theater about raising the debt limit.

But it seems to me that larger historical events and actions have swept educated and uneducated people alike into a dangerous current. The Iraq War and the Financial Crisis would have been fertile grounds for a populist uprising no matter the quality of our education system. The digital age has scrambled how we process information, causing epistemic vulnerabilities across the board while amplifying the political extremes.

In the long-term, a better education system can make a difference. Arguably, the whole point of our public school system is to instill civic education and civic virtue. We haven’t been focused on this priority. We can do better.

In the near-term, preservation of self-government depends on whether this generation’s citizens and political leaders can navigate a major storm while keeping the Constitution intact.

Links and News

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar wrote a short but moving reflection about living life in his seventies.

The surgeon general issued a warning about the link between social media and youth mental health.

The Free Press: The Parents Saying No to Smartphones

Matt Yglesias is writing an ongoing series about the “strange death of education reform.” Part one is a historical overview. Part two is about the achievement gap. Part three is about charter schools. Part four is about how the political right abandoned reform efforts in favor of privatization. Part five is about why the teacher evaluation reforms flopped. (Most public schools are still using time-intensive teacher evaluation tools, even though research has shown that these evaluation tools have no impact on student outcomes.)

Fun with history: This is a cool article in the Daily Sun about a group of eighth grade students from Northland Preparatory Academy in Flagstaff who are participating in the National History Competition in Maryland. They will present a documentary comparing three gold rushes in U.S. history. The project started at the school site level, then the students won second place at a statewide competition to make the national finals. “The state winners in Arizona attended a day-long event at the Arizona Historical Society Museum in Tempe earlier this month, where they got to tour the archives and work with historians to edit their projects.”